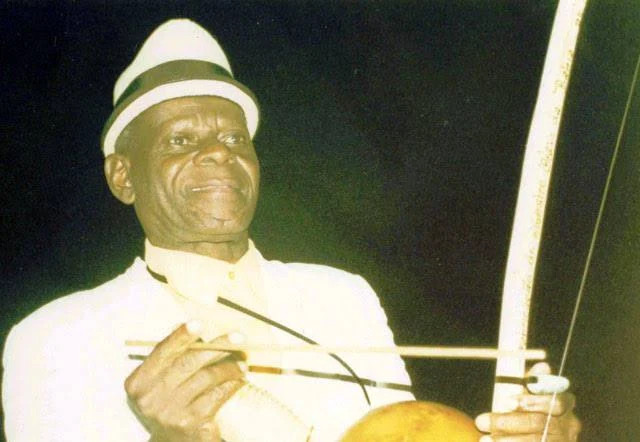

Mestre Quinzinho

- Lived in: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil

- Date of Birth: 01-Jan-1925

- Date of Death: 01-Jan-1950

- Learned from:

- Capoeira Style: Angola

Biography:

Joaquim Felix, known in the Rio streets as Quinzinho, is one of those shadowy figures who sits at the crossroads of malandragem, street violence, and the old carioca capoeira of the gangs—a kind of capoeirista whose name survives not through formal academies, but through prison memory, street testimony, and the oral history of those who lived that world.

Quinzinho lived fast and dangerously. Contemporary references describe him as a young outlaw and gang leader, already carrying deaths on his conscience and having served time in a penal colony. Decades later, his name still appears alongside “legendary bandits” in Brazilian prison lore—mentioned, for example, in Drauzio Varella’s Estação Carandiru (1999), where Quinzinho is remembered as part of the criminal mythology passed down inside the system.

Yet Quinzinho was not only feared—he was also recognized as a capoeirista, and in that role he became the first teacher of Mestre Leopoldina. Around 1950–1951, when Leopoldina was about 18 and hungry to learn, he encountered Quinzinho in the rough orbit of Central do Brasil, train lines, and the street network of Rio’s “rogues.” Their first contact was tense and nearly tragic: Leopoldina describes being humiliated (Quinzinho stealing his hat, taunting him) and becoming so furious he went to retrieve an 8-inch knife hidden under the train tracks, intending to deliver what he called a “facada conversada”—a “conversational stab,” done face-to-face to preserve status in the logic of jail and malandro honor. A newsboy called Rosa Branca calmed him down, and violence was avoided.

Later, when Leopoldina ran into Quinzinho again at a bus stop—surrounded by other street figures—Quinzinho’s behavior revealed something essential about his authority. Seeing Leopoldina was respected among the malandragem, Quinzinho approached to prevent conflict, but still searched him for weapons (“deu uma geral”), asserting control the way a street leader would. It’s a small scene, but it shows the kind of man Quinzinho was: dangerous, calculating, and always operating with survival instincts.

Over the following weeks, Leopoldina carefully worked up the courage to ask what he truly wanted: to learn capoeira. Quinzinho’s response was direct—“Go to Morro da Favela tomorrow.” For Leopoldina, this invitation felt like winning a fortune. The training, however, was brutal in the way street capoeira often was: Leopoldina returned home wrecked, unable to get out of bed, afraid Quinzinho would reject him if he missed the next session. But Quinzinho surprised him with a kind of tough acceptance—“It’s okay… it’s okay”—and continued teaching.

Quinzinho’s capoeira was tiririca: a form of capoeira without berimbau, practiced among the street gangs and malandros of Rio, descended from the older violent traditions of the 1800s maltas. He didn’t teach through a structured academy method like Bimba’s sequences in Bahia or Sinhozinho’s approach in Rio. Instead, as Leopoldina describes it, Quinzinho taught by playing with the apprentice and correcting in the moment—“Do it like this… do it like that.”

And here comes the paradox that makes Quinzinho historically fascinating: even as an outlaw, he could embody a strict “mestre ethic.” In one powerful episode, a man named Juvenil tried to dominate Leopoldina in a game, throwing a dangerous kick that grazed his head. Quinzinho—sitting with a pistol tucked at his waist—stood up and put the gun in Juvenil’s face and warned him not to do that, because it would make the beginner afraid and unable to learn. In an era when beginners often learned by being beaten “to get smart,” Quinzinho enforcing that line is striking. It suggests that, inside the violent street world, he still held a code: capoeira was not only about hurting—it was also about forming malícia, courage, and readiness.

Quinzinho’s end fits the pattern of his life. According to the account you provided, he was arrested again and later murdered in prison on Ilha Grande, killed by a security chief known as Chicão. After that, Leopoldina disappeared for a time out of fear of reprisals from rival criminals, before later returning to capoeira through Mestre Artur Emídio and the berimbau-driven Bahian style.

In capoeira history, Quinzinho represents something older than the academy: the capoeira of the malandros, born in the street, shaped by honor codes, survival, and the constant threat of violence—yet still capable of producing discipline, mentorship, and deep “capoeira intelligence.” He may not have left a formal lineage the way later mestres did, but through Leopoldina’s testimony, Quinzinho remains remembered as a rare and complex figure: the outcast who was also a master.