Capoeira

Capoeira is an Afro-Brazilian martial art that unites combat, dance, acrobatics, music, ritual, and oral tradition into a single living cultural system. Practiced inside a circle known as the roda, capoeira unfolds as an ongoing dialogue between two players rather than a conventional fight. Constant movement, strategic deception, and mutual awareness define the exchange, making intelligence, perception, and timing as important as physical strength.

Unlike martial arts based on rigid stances or direct confrontation, capoeira emphasizes fluidity, adaptability, and continuous motion. At its foundation lies the ginga, a rhythmic rocking step that keeps the body in constant movement, concealing intention while maintaining readiness to attack or evade. From the ginga emerge kicks, sweeps, evasions, inverted movements, and acrobatics, linked together in uninterrupted sequences that blur the line between offense and defense.

Often described as a fight disguised as a dance, capoeira is far more complex than camouflage alone. It functions simultaneously as self-defense, social ritual, musical expression, and historical memory. Knowledge in capoeira is transmitted through embodied practice rather than written instruction, allowing history, philosophy, and identity to be carried forward through movement, rhythm, and shared experience.

Origins

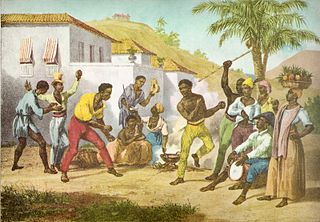

The history of capoeira begins in colonial Brazil, shaped directly by the transatlantic slave trade and the forced displacement of millions of Africans. From the 16th century onward, Portugal transported enslaved peoples primarily from West and West-Central Africa to work on sugarcane plantations, in mines, and in growing urban centers. Alongside their labor, these Africans carried sophisticated systems of combat, movement, music, and ritual knowledge.

Within an environment defined by violence, cultural suppression, and deliberate fragmentation of African communities, traditions were not erased but transformed. Capoeira emerged as a creative and practical response to oppression, combining African combat games with strategies necessary for survival in colonial Brazil. Because capoeira was preserved through oral transmission and physical practice, its early development remains the subject of historical debate.

Despite differing interpretations, scholars broadly agree that capoeira is a Brazilian-born art form deeply rooted in African traditions. It was neither imported intact from Africa nor created in isolation in Brazil. Instead, capoeira took shape through adaptation and resistance, influenced by African heritage, Indigenous presence, and the harsh social realities of colonial life.

African Roots

Angola occupies a central place in capoeira’s historical memory, oral tradition, and musical language. A large proportion of the Africans forcibly brought to Brazil came from Central West Africa, particularly regions corresponding to present-day Angola and the Congo. Early practitioners commonly referred to the art as jogo de Angola or brincar de Angola, preserving an explicit link to African ancestry.

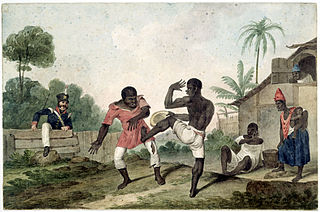

One African combat tradition most frequently associated with the origins of capoeira is engolo, practiced among the Nyaneka-Nkhumbi peoples of southern Angola. Engolo is characterized by circular play, inverted kicks, sweeps, evasions, and ritualized competition—elements that closely resemble the technical and aesthetic vocabulary of capoeira. Mid-20th-century ethnographic research and visual documentation reinforced this connection.

While engolo is not capoeira itself, contemporary scholarship supports the view that capoeira inherited core technical principles and philosophical approaches from such African martial traditions. These practices were reshaped in Brazil, absorbing influences from multiple African cultures, Indigenous knowledge, and urban street life, ultimately forming the distinct art known today as capoeira.

Quilombos

Throughout the colonial period, enslaved Africans in Brazil endured brutal labor systems, corporal punishment, and legal structures designed to suppress resistance. In response, survival strategies ranged from cultural preservation to open revolt. Capoeira functioned within this context as both a method of physical defense and a way to sustain identity, dignity, and collective memory.

Escaped enslaved people formed independent settlements known as quilombos in remote and difficult-to-access regions. These communities became centers of resistance and cultural continuity, developing systems of collective defense against colonial militias. Historical accounts describe quilombo fighters employing agile, deceptive combat techniques that frustrated better-armed opponents.

Although it remains debated whether capoeira in its recognizable form was practiced in quilombos such as Palmares, the conditions of resistance, warfare, and survival that defined quilombo life profoundly shaped capoeira’s emphasis on mobility, strategy, and adaptability.

Urbanization

By the 18th and 19th centuries, capoeira had spread into Brazil’s major cities, including Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, and Recife. In these urban environments, enslaved and free Black populations practiced capoeira in streets, docks, markets, and communal spaces. The art adapted to city life, incorporating ambush tactics, collective awareness, and familiarity with weapons.

In Rio de Janeiro, organized groups known as maltas emerged, developing territorial identities, symbols, and hierarchies. Capoeira became intertwined with political violence and street conflict. Police records from the period describe frequent clashes involving capoeiristas armed with razors, knives, or sticks.

As a result, authorities increasingly viewed capoeira as a threat to public order. Practitioners were arrested, whipped, imprisoned, or forcibly conscripted, reinforcing capoeira’s reputation as both dangerous and formidable.

End of slavery and prohibition of capoeira

After the abolition of slavery in 1888, formerly enslaved people were legally freed but socially abandoned. Economic exclusion, racism, and marginalization defined the post-abolition era. Capoeira, closely associated with Black identity and resistance, became a prime target of repression.

In 1890, the Brazilian Republic outlawed capoeira nationwide. Practicing capoeira became punishable by imprisonment, forced labor, and violence. The art survived underground through secrecy, coded behavior, and the use of apelidos to protect practitioners.

Despite decades of persecution, capoeira endured as a living tradition, particularly in Bahia, where its cultural foundations remained strong.

Systematization of the art

In the early 20th century, shifting political conditions allowed efforts to reorganize capoeira. Some sought to present it as gymnastics or self-defense, minimizing ritual elements to gain acceptance.

A turning point occurred in the 1930s when Mestre Bimba developed Luta Regional Baiana, introducing structured training, discipline, and pedagogy. His work reframed capoeira as a respectable practice and led to legalization.

In response, Mestre Pastinha founded a school devoted to preserving traditional capoeira, emphasizing ritual, strategy, and African philosophical continuity. This approach became known as Capoeira Angola.

Styles

Capoeira today is commonly described through three broad styles: Angola, Regional, and Contemporânea. Capoeira Angola emphasizes tradition, ritual, and strategic dialogue close to the ground.

Capoeira Regional reflects Mestre Bimba’s reforms, focusing on structured training, speed, and efficiency. Capoeira Contemporânea blends elements of both approaches, often incorporating acrobatics.

Despite stylistic differences, all forms of capoeira share the roda, music, and embodied philosophy that define the art.

Music

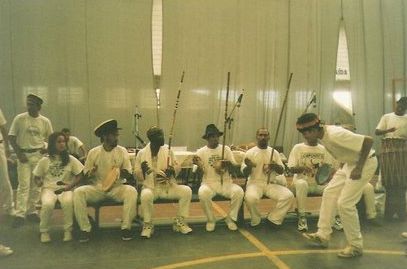

Music is inseparable from capoeira and determines the rhythm, style, and ethics of the game. The bateria creates the structure and atmosphere of the roda.

Led by the berimbau and supported by percussion, capoeira music guides movement and interaction.

Through song, capoeira preserves history, moral instruction, and collective memory.

Song Structure

Ladainha

The ladainha opens the roda as a reflective solo.

Its stable melody emphasizes meaning over variation.

Louvação

The louvação introduces collective praise.

It prepares players to begin the game.

Corrido

Corridos interact dynamically with the game.

They respond to events in real time.

Quadra

Quadras were introduced by Mestre Bimba.

They emphasize clarity and pedagogy.

Today

From the mid-20th century onward, capoeira spread globally as mestres traveled to teach and perform.

Today, capoeira is practiced worldwide as a martial art, cultural expression, and social practice.

UNESCO’s 2014 recognition affirmed capoeira as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

UNESCO Recognition

UNESCO recognized capoeira as a cultural system.

Learning occurs through participation.

Capoeira remains a living archive of resistance.